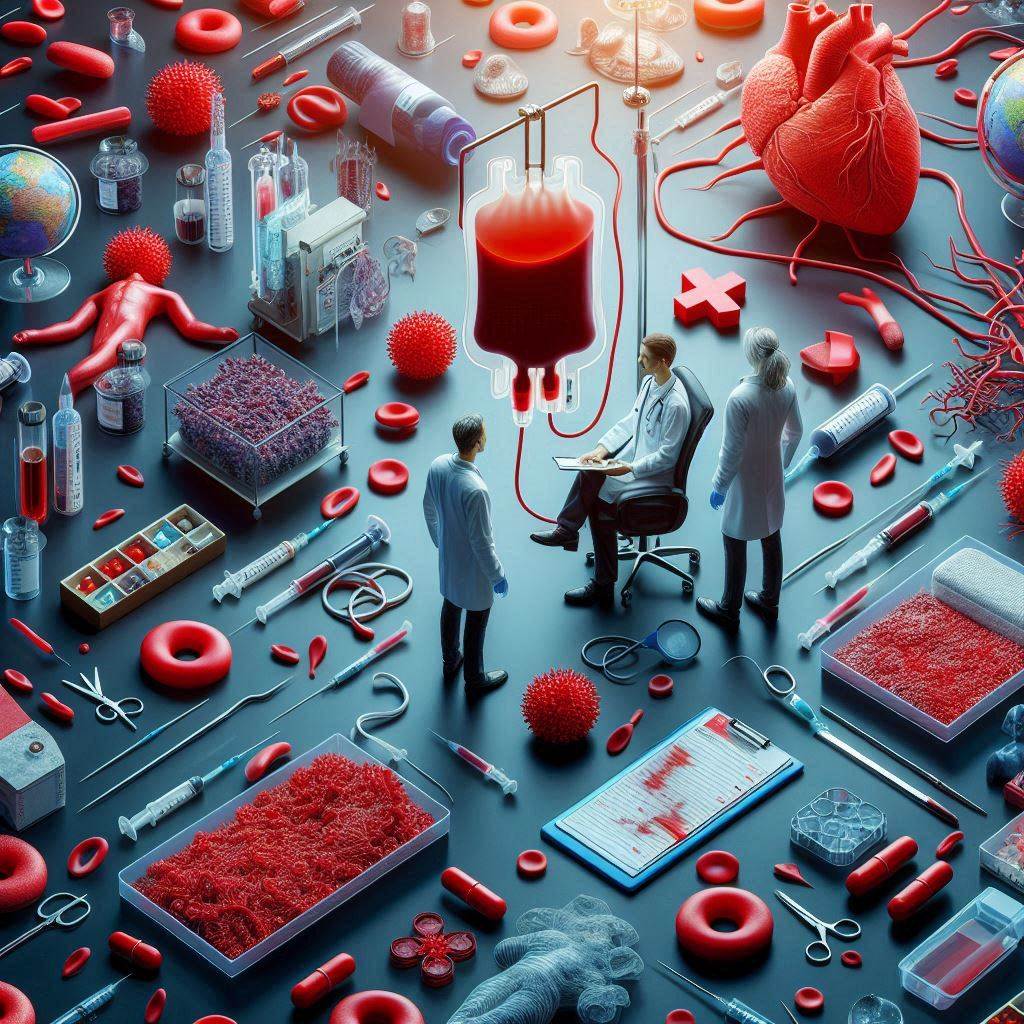

Picture a system built to save lives—sterile halls, nurses in white coats, bags of crimson hope filling the shelves of blood banks. Now imagine that same life-saving system becoming a silent vehicle of death. In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, before the world fully grasped where did AIDS come from, blood banks unknowingly became one of the key channels for its spread.

This is the untold story of how AIDS and blood transfusions intersected, and how uncertainty about the virus’s origin allowed tragedy to seep into hospitals, clinics, and operating rooms across the world—especially in North America.

The Invisible Intruder in Donated Blood

It was viewed as sterile, life-saving, and tightly regulated. No one thought that a microscopic enemy could hide inside it, undetected, and turn the very act of saving a life into an act of infection.

But it did.

Before HIV had a name—or a test—blood transfusions became an invisible bridge for the virus to enter the bodies of unsuspecting patients. People undergoing surgeries, accident victims, hemophiliacs who required regular clotting factor injections—all were at risk. Thousands were infected before anyone realized what was happening.

At that point, the burning question was not only where did AIDS come from, but also: how had it entered systems designed to heal?

The Hemophilia Community: A Devastating Toll

One of the hardest-hit groups during the blood-related transmission crisis was the hemophilia community. This pooling process, intended to stabilize blood products, turned deadly when just one HIV-infected donation could contaminate an entire batch.

For hemophiliacs, the consequence was catastrophic. had been exposed to HIV. These were individuals with no behavioral risk factors, simply reliant on modern medicine to manage a genetic disorder.

As families began to lose loved ones, the pressure mounted to answer: Where did AIDS come from, and how did it end up in blood?

Delay, Denial, and Distrust

A major tragedy of this chapter in the AIDS story was the delay in action. Blood banks and plasma centers resisted widespread HIV testing or screening of donors in the early 1980s. Part of the reason was fear—fear of creating panic, of losing donors, of collapsing public confidence in blood supply systems. Another part was simply ignorance. Without a clear understanding of where AIDS came from, institutions hesitated to act decisively.

It wasn’t until 1985—four years after the first official AIDS cases in the U.S.—that the first HIV blood test was licensed. Only then could donated blood be reliably screened for the virus. For many, it was too late.

A Turning Point: Reforming Blood Safety

The AIDS crisis transformed the blood donation landscape forever. Strict donor eligibility criteria have been enforced to minimize risk. Systems are in place to track, recall, and investigate any contamination concerns.

But behind every regulation lies the memory of lives lost in silence—patients who died not because medicine failed them, but because knowledge came too late.

Revisiting the Origin: Lessons from the Past

When we ask where did AIDS come from, we must go beyond the forests of Central Africa or the primate-to-human transmission of SIV. We must also examine the social and institutional failures that allowed HIV to spread unchecked for years.

Blood banks, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies were caught unprepared—not because they didn’t care, but because they didn’t understand the scale of what was coming. The virus exploited systems of trust, moving quietly until it erupted into a full-blown epidemic.

The intersection of AIDS and blood banks is a tragic reminder that even the safest institutions can become pathways for harm if vigilance lapses. It reinforces the urgent need to understand where did AIDS come from—not just biologically, but structurally and socially.

Today’s advanced blood screening techniques stand as a testament to hard-earned lessons. But they also carry a warning: in the battle against infectious diseases, ignorance and delay are as dangerous as the pathogens themselves.