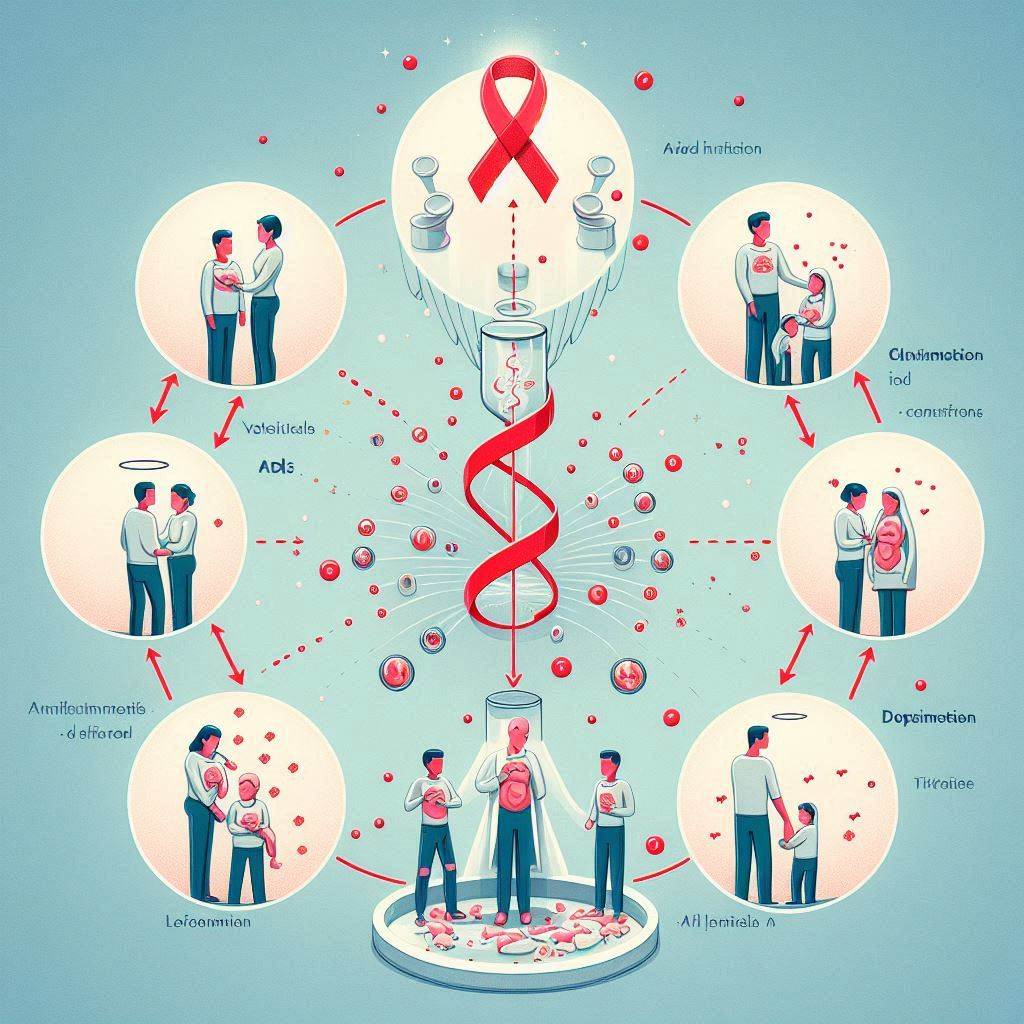

Imagine a mother holding her newborn child—an image of innocence, love, and protection. Now imagine an unseen threat quietly crossing from mother to child, not through neglect, but through biology. This is the heartbreaking reality of vertical transmission of HIV, a route through which the virus silently travels from one generation to the next.

In the global quest to understand where did AIDS come from, one of the most critical and emotional aspects has been the realization that HIV does not discriminate—not even against infants. Vertical transmission reveals not just the scientific complexity of the virus, but also the deeply human toll it has taken on families across the world.

What Is Vertical Transmission?

Without medical intervention, the risk of transmission can range from 15% to 45%, depending on the mother’s health, access to treatment, and feeding practices.

In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, especially before the virus was fully understood and treatment options were limited, thousands of children were born with HIV. For many families, this was how they first encountered the virus—through a diagnosis they never expected.

The question “where did AIDS come from” became more personal than ever for mothers watching their children suffer from a disease they didn’t even know they carried.

The Early Impact: Silence and Loss

In the 1980s and early 1990s, many pregnant women—especially in low-income areas—were unaware of their HIV status. Testing was not always available or offered. Even when it was, the fear of stigma kept many from seeking help. As a result, babies were born already carrying the virus, often without any immediate symptoms.

These children, labeled “pediatric AIDS cases,” would soon fall ill with infections, growth delays, and developmental issues. Their parents were left devastated, asking not just “how,” but “where did AIDS come from,” and why had it taken root in the most vulnerable lives?

In sub-Saharan Africa, the crisis was especially severe. Entire generations were affected. In some countries, pediatric AIDS became one of the leading causes of child mortality. Hospitals filled with tiny patients, and families were torn apart by a virus passed silently through love.

Science Intervenes: Breaking the Chain

As researchers learned more about HIV’s lifecycle, they discovered ways to interrupt vertical transmission. In 1994, a groundbreaking study known as ACTG 076 revealed that the drug AZT (zidovudine), when given to pregnant women and their newborns, could reduce the risk of transmission by nearly 70%.

This was a turning point.

Today, with effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), the risk of vertical transmission can be reduced to less than 1%—a remarkable achievement in modern medicine.

But access remains uneven. In many parts of the world, especially in developing nations, women still lack the resources or support needed to protect their children. Thus, the question where did AIDS come from remains both a biological inquiry and a matter of global inequality.

Beyond Biology: The Emotional Burden

For HIV-positive mothers, the fear of passing the virus to their child is a constant emotional weight. Even when treatment is available, anxiety and guilt often linger. Vertical transmission is not just a scientific term—it’s a deeply human experience filled with hope, fear, and resilience.

Programs that offer counseling, nutrition, prenatal care, and safe breastfeeding alternatives have proven essential in supporting these mothers and protecting the next generation.

The story of vertical transmission and AIDS underscores how far we’ve come—and how far we still need to go. It is a reminder that understanding where did AIDS come from is not just about identifying a virus in the wild, but about tracking its path through the most sacred of human connections.

Thanks to advances in science and the courage of mothers worldwide, the dream of an AIDS-free generation is now within reach. But we must continue to fight—not just the virus, but the barriers that allow it to thrive in silence.

In every mother’s heartbeat, and every child’s breath, the promise of that future lives on.