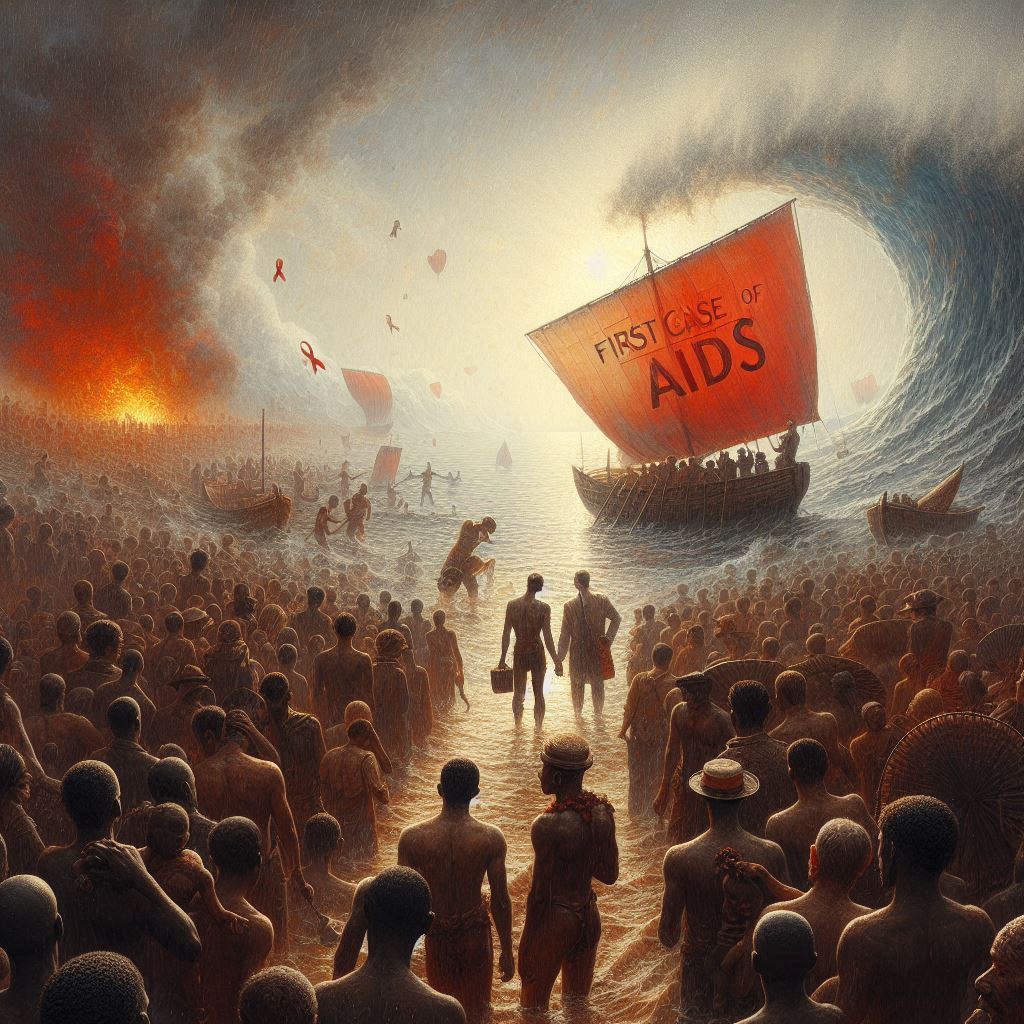

Picture this: A single, flickering flame in the vast darkness of medical history. But this flame would grow into a global inferno. That flicker was the first case of AIDS—the beginning of a long and devastating story. To understand it, we must explore the mystery of where did AIDS come from, tracing its earliest footsteps in a world unprepared for what lay ahead.

The earliest known evidence of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, lies frozen in time. He wasn’t known to be seriously ill, nor did he show signs of a disease that didn’t yet have a name. But decades later, scientists would return to that blood sample with modern tools and make a chilling discovery: it contained HIV-1, the most aggressive strain of the virus.

This 1959 sample is now widely considered the first documented case of AIDS, even though the term “AIDS” wouldn’t be coined until 1982. It’s as if the past left a hidden clue in a bottle, buried deep in the sands of time, waiting to be uncovered.

Silent Transmission Before the Storm

To fully grasp where did AIDS come from, we must understand that the virus didn’t explode onto the global scene overnight. Between the 1920s and the 1960s, HIV was already spreading among human populations in Central Africa. But with limited medical technology and understanding, it went unnoticed—masked as tuberculosis, wasting syndrome, or other more familiar conditions.

The virus moved through river ports, mining camps, sex trade routes, and growing cities. In places like Kinshasa, with its expanding railways and colonial-era infrastructure, HIV found fertile ground to spread unnoticed.

Another Early Echo: The Manchester Sailor, 1959

Around the same time as the Kinshasa discovery, another intriguing case emerged. A British printer and former sailor named David Carr died in Manchester in 1959, suffering from a mysterious illness marked by pneumonia, weight loss, and immune collapse. For years, his case puzzled doctors. Later tests in the 1980s found fragments of HIV in his preserved tissues, although the findings remain debated.

Still, the case of Carr—if accurate—adds another dot on the early AIDS timeline. It suggests that HIV had already left Africa and arrived silently in the West, like a ghost ship docking under cover of night.

A Child in St. Louis: Robert Rayford, 1969

In 1969, a 15-year-old African-American boy named Robert Rayford died in St. Louis, Missouri, of a disease that ravaged his immune system. Years later, tissue samples from Rayford tested positive for HIV, making him one of the earliest confirmed cases in the United States. But no one at the time had any concept of AIDS—it would be another 12 years before the disease made headlines.

Rayford’s tragic story adds another layer to the question of where did AIDS come from—a reminder that the virus was already creeping into the American bloodstream long before anyone realized.

A Virus Without a Name

Before 1981, AIDS didn’t have a name, a pattern, or a place in textbooks. People were dying of rare infections, aggressive cancers, and unexplained immune collapse, but the dots weren’t connected. The virus was invisible, weaving through communities and countries like smoke slipping through cracks.

Then, in 1981, the U.S. The modern AIDS epidemic had finally come into focus—but it had been quietly unfolding for decades.

A Hidden Spark in the Shadows

So, what does the first case of AIDS teach us about where did AIDS come from? It reveals a virus that didn’t burst onto the scene—it crept in, changed shape, and quietly rewrote the rules of infection. From the jungles of Central Africa to the blood of an unknown man in Kinshasa, and from a teenage boy in Missouri to an Englishman in Manchester, HIV had already begun its deadly journey before anyone could even see it coming.

Understanding the first case is like holding a lantern to a dark corridor of history. It shows us not only how far the virus has come—but how long it was with us before we ever noticed.

And in answering where did AIDS come from, we gain more than knowledge. We gain vigilance, humility, and a reminder that even the greatest storms often begin with a single, silent spark.